Nopales: Eating an Icon of the Desert

When you imagine eating prickly pear, your mind probably flashes to bright pink. You’re thinking of the fruit — called "tuna" in Spanish — not the plant itself. But did you know you can eat the cactus pads too? Those ubiquitous desert cactuses are food!

The young, tender paddles are not only edible, they’re delicious, nutritious and have sustained desert peoples for millennia.

Nopales — the young, tender pads of the prickly pear cactus — are a vibrant, versatile ingredient that has long nourished the people and ecosystems of the Southwest. With a tangy flavor, okra-like texture and ultra-low water needs, nopales are more than just an iconic desert plant — they’re a living legacy of Indigenous foodways and a desert-adapted crop ready for a broader culinary comeback north of the border.

Known as "nopales" in Spanish and "nopalitos" when diced and cooked, these cactus pads appear in spring and have been a staple for Indigenous and Mexican populations for over 10,000 years. Their recent resurgence in restaurants and home kitchens is a testament to their culinary and cultural value.

Keep reading to discover:

Why nopales are a heritage food of the Sonoran Desert

Their nutritional and environmental benefits

Where to get some in Arizona

How to cook with them at home

Why eating nopales is good for Arizona

How the Prickly Pear Cactus has Grown to Fit Arizona

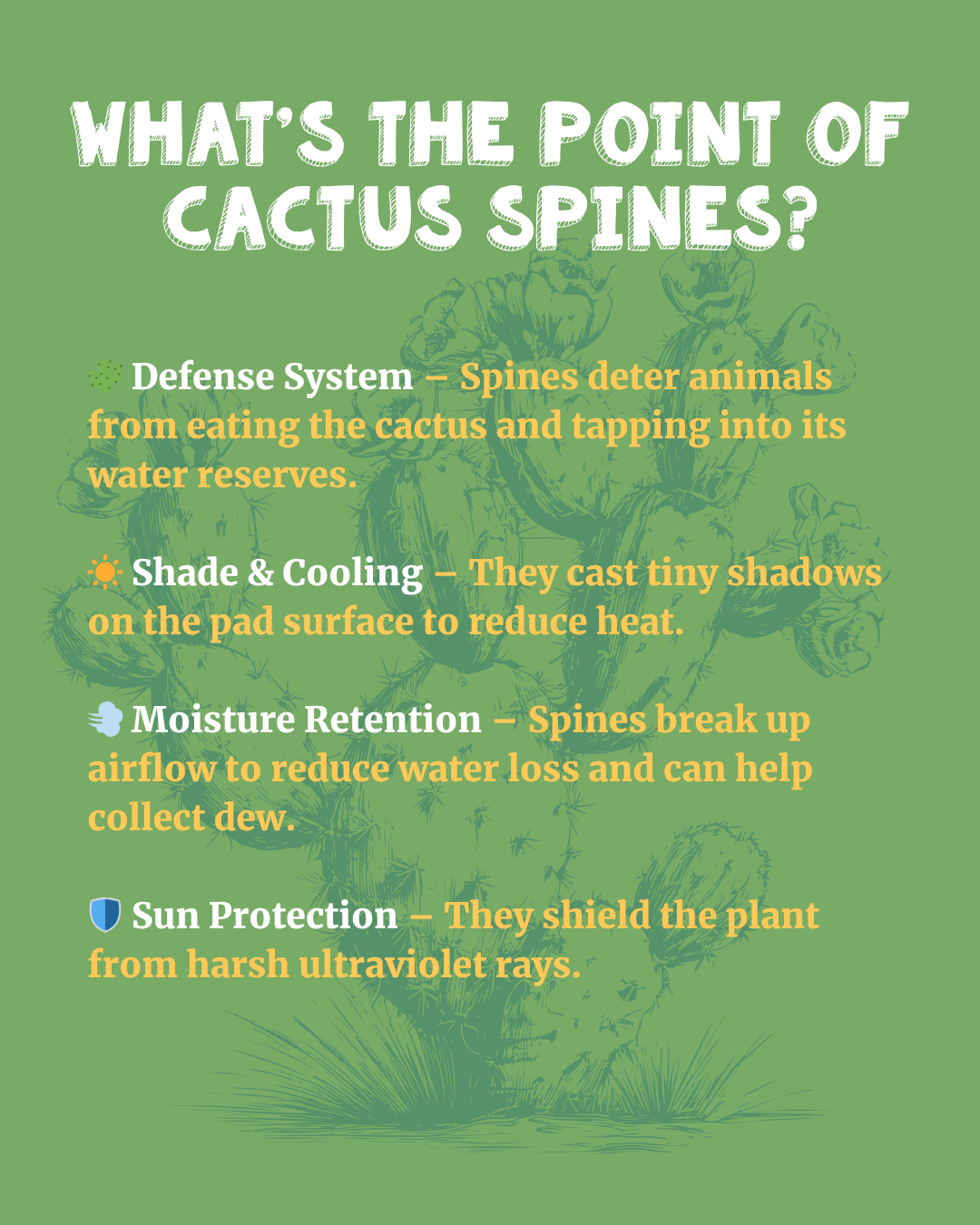

Prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) is one of the most iconic plants in the Sonoran Desert — for good reason. They are ubiquitous in Arizona’s deserts because the plant is brilliantly adapted. Its flat, paddle-like pads grow in segments and are covered with protective spines. These pads are actually modified stems—flattened rather than rounded—to better perform photosynthesis and store water.

Even the orientation of the pads helps the plant survive. Prickly pear pads often grow with their flat surfaces facing east-west and their narrow edges facing north-south. This helps them absorb sun in the cooler mornings and evenings, while minimizing exposure during the hottest part of the day.

With all of these adaptations, prickly pear are an ideal food crop that use very little water. In fact, nopales thrive with minimal to no supplemental water once established — just natural rainfall.

A Heritage Crop of the Desert Southwest

For over 10,000 years, Indigenous peoples of the Americas have relied on prickly pear for both food and medicine. In the desert Southwest, Native groups including the Cahuilla, Akimel O’odham, and Tohono O’odham have traditionally harvested the young cactus pads.

Young paddles were sliced and grilled, boiled, dried, or added to stews. They were also used medicinally to treat wounds, stomach issues, and inflammation. The magenta fruits were prized for their sweetness and moisture. Both the pads and fruit were preserved for year-round use — by sun drying, roasting, or turning into syrup.

Beyond Arizona, prickly pear is also grown widely in the Canary Islands, Morocco, and Mediterranean regions, valued for its drought tolerance, health benefits, and culinary flexibility. Today, chefs and growers are helping reclaim and revitalize these traditions, integrating nopales into modern diets and regenerative agriculture practices.

A Nutritional Powerhouse

At only 14 calories per cup of raw nopales, they are low in calories and high in nutrients, including:

Fiber – supports digestion and helps regulate blood sugar

Vitamin C & A – boost immune health and skin integrity

Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium – essential for bone and heart health

Mucilage (soluble fiber) – helps manage cholesterol and blood sugar

Traditional Mexican medicine has long celebrated nopales as a folk remedy for diabetes. Recent studies confirm that just 100 grams a day — about two pads — can help manage type 2 diabetes and reduce insulin needs in type 1 diabetics.

One cup of raw nopales provides 13% of the recommended daily value of vitamin C, 13% of calcium, and 11% of magnesium. They’re also low in saturated fat and cholesterol, making them a great addition to many diets.

Where to Eat Nopales in Arizona

You don’t need to forage to enjoy nopales—many Arizona chefs are embracing this sustainable ingredient:

Amelia’s (Tucson)

El Nopalito (Phoenix)

JUNTOS (Phoenix)

TJ Farms (Waddell/Phoenix)

Food City and other Latino grocers

JUNTOS’s Tlacoyo con Nopal

Cooking Methods

Raw in salads or salsas

Boiled or sautéed with eggs or onions

Grilled or roasted whole

Steamed and added to soups or stews

Pickled, canned, or dehydrated for year-round use

Great in tacos, tostadas, scrambled eggs, salads, and alongside meat dishes

Some people find nopales to be slimy, depending on the preparation. The slime, or mucilage, protects the plant from losing moisture; for humans, this is soluble fiber that helps regulate blood sugar and support digestion. Grilling or curing in salt can get rid of the slime; so can boiling with plenty of salt. Reportedly throwing an onion into the pot also helps with slime, and it adds extra flavor, too.

How to Forage

All young prickly pear pads are edible, but those from Opuntia ficus-indica are especially tender and easy to clean. They must be harvested in spring before the interior becomes woody.

Look for young, firm, bright green pads with minimal spines—mid-morning is ideal for harvesting, when acid content is lowest. While wearing thick gloves, hold the pad with tongs and cut it about 1 inch above the joint where it connects to the next pad.

How to Prepare

Wear gloves. Scrape off spines and trim edges with a knife.

Rinse well and check under bright light to ensure all spines and glochids are removed.

Remove the eyes where the spines were, then use a vegetable peeler to peel all sides.

Slice or dice for recipes.

Cook to reduce mucilage (slime):

Boil with salt and onion, then rinse

Cure in salt to draw out slime

Once cooked and slightly dried out, the mucilage becomes far less noticeable.

A Delicious, Sustainable Future

Nopales are more than just a prickly plant—they’re a culinary bridge to Arizona’s past and a path toward a more climate-resilient future. With deep roots in Indigenous foodways and modern relevance in health and sustainability, nopales deserve a spot on every table.

By supporting nopal growers and enjoying this desert delicacy, you’re contributing to a regional food system that honors tradition, restores the land, and celebrates the flavors of the Sonoran Desert.