5 Takeaways from the USDA's Recent Census of Agriculture … and What They Mean for Arizona

The recently released 2022 Census of Agriculture reflects what many farmers and food system advocates have been voicing for decades: increasing consolidation and concentration within the U.S. food system, squeezing small and mid-sized farms out of business.

Every five years, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) publishes a Census of Agriculture that shares data related to the farms and ranches in the United States and the people who operate them. Since 1840, the USDA has conducted surveys on US farms, defined as an operation that produced and sold $1,000 or more of agricultural products in a year.

The Census of Agriculture is a snapshot of the state of the country’s farming and food system; it looks at land use and ownership, operator characteristics, production practices, and income and expenditures. The Census helps to tell the story of agriculture, albeit with its own limitations. The data collected and analyzed impacts where government resources are distributed and the policies and programs that are created.

Below are five key takeaways from the 2022 Census of Agriculture, and what they reveal about critical issues and potential opportunities for the nation’s – and Arizona’s – agricultural system.

1. The U.S. food system is at unprecedented levels of consolidation and concentration

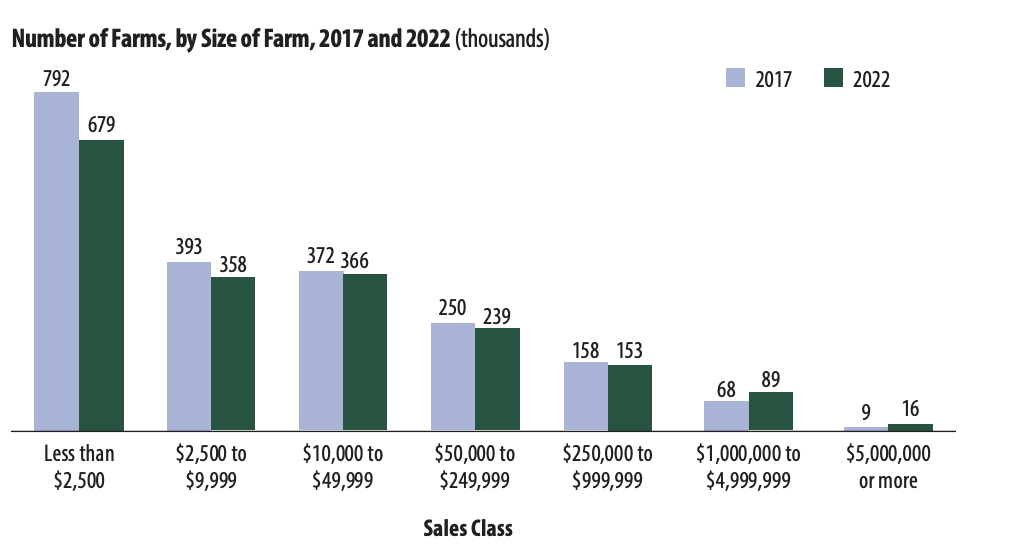

Farm numbers are continuing to dwindle, while the average size of farms continues to increase. Between 2017 and 2022, the country lost 142,000 farms, or 7%, and the steepest decline was among the smallest farms with less than 10 acres. In fact, farm numbers decreased in every size category except one: those operating 5,000 acres or more.

Since 2017, the nation has lost 34% of dairy farms, 8.5% of hog farms, and 7% of beef cattle farms. Small and mid-sized farms have declined rapidly while the number of large farms increased. Large farms – which include mega operations with hundreds of thousands of acres – account for only 4% of the total number of farms, but control two-thirds of U.S. agricultural land.

From an economic perspective, the largest farms – with sales of $5 million or more – account for fewer than 1% of total farms but 42% of all sales. This has increased from 35% in 2017. Similarly, 75% of the country’s total value of agricultural production now comes from farms with $1 million or more in sales. The “get big or get out” policies have pushed more small and mid-size farmers out of business over the past five years, more so than in any other Census period.

Across the US, farmland is also being lost. In 2017, there were 900 million acres of farmland, but according to the recent census data, this has dropped to 880 million acres.That’s a landmass the combined size of every state in New England, except Connecticut. Twenty million acres of farmland were taken out of active production to make way for urban sprawl, solar farms, and other industrial development.

The landscape of US agriculture is becoming increasingly more consolidated, concentrated, and dominated by factory farming operations. While small and diverse farms are going out of business, corporate-controlled farms are thriving, with the help of federal subsidies and farm bill programs.

2. The average age of farmers is still high, but new and young(er) farmers are on the rise

American farmers are continuing to get older; the average age of a U.S. farmer is now 58, up slightly from the previous census. However, nearly a third of the 3.4 million producers in 2022 were beginning farmers (those with 10 or fewer years of experience), an 11 percent increase since 2017. Their average age was 47, and their farms were smaller than average in terms of both acres and sales. There was also an increase of nearly 33,000 farms owned or leased by beginning farmers.

The census data showed a 7% increase in farmers under 44, with the largest jump among the youngest producers, those under 25 years of age. Meanwhile, the number of producers under age 35 was slightly less than 300,000, comprising 9% of all producers.

3. Farming is not a viable livelihood for many

Farming does not pay the bills for the majority of farmers and ranchers. Sixty-eight percent of producers have off-farm jobs to make ends meet. The structure of our current food system – highly consolidated – has a lot to do with that.

While there have been increases in total value of crops by 45 percent and livestock by 35 percent since 2017, 75% of that was produced by fewer than 6% of farms. These same 6% of farms brought in annual revenues of about $1M and saw their profit margins increase the most.

Meanwhile, small farms ($50,000 or less in sales) made up 74% of all farms and yet only contributed to 2% of all sales in 2022.

Net farm income in 2024 is projected to be less for US producers. When adjusted for inflation, net farm income – a broad measure of farm profitability – is expected to decrease 27%, or $43B, from 2023. Much of the forecasted decline in 2024 is tied to lower crop and livestock cash receipts and continued increases in production costs.

4. Black farmers are decreasing while Hawaiian and Pacific Islander farmers are increasing

One of the most concerning statistics to come out of the 2022 Census was the loss of Black farms. Farms with at least one producer reporting as Black decreased by 13% between 2017 and 2022, the highest decline among all racial groups. In spite of this and documented decades of discriminatory USDA policies, Black farmers acquired more total farm acreage, with an increase from 4.6M in 2017 to 5.3M in 2022, and a new generation of Black farmers are still entering the agricultural industry.

An upward trend noted in the census data is the increasing numbers of Hawaiian and Pacific Islander farmers, which has jumped by 13%, with a 50% increase in beginning producers (1,509 in 2022 compared with 1,007 in 2017). This may partly reflect a revival in Native Hawaiian farming practices and the Land Back movement.

5. Agriculture is providing economic growth & stability across Indian Country

Agriculture continues to be one of the leading economic development drivers in Indian Country, according to a 2022 Census key findings report released by the Intertribal Agriculture Council.

Over the past five years, Native producers nearly doubled economic revenues from $3.6B in 2017 to $6.4B in 2022, despite the pandemic, economic downturns, and severe climate challenges. Crop production also increased almost twofold – from $1.43B in 2017 to $2.78B in 2022. More Tribal farmers, according to census data, identified their primary source of income coming from farming rather than off-farm employment.

Tribal communities are also reclaiming stewardship of land, and the number of acres in production has increased by 5M since 2017. The average age of a Native producer, 56, is also lower than the national average of 58 years old.

Limitations & Implications of the Ag Census

While the census can be seen as a comprehensive survey, it only represents those that voluntarily choose to respond to the survey, speak the language in which the survey is delivered, have time to complete it, and meet the definitions used in census categories and data parameters.

The response rate for the 2022 Census of Agriculture was 61% with a large portion of the responses, over 40%, being submitted online. The census, therefore, does not represent U.S. agriculture and its diverse producers in its entirety.

The census data also lacks a more in-depth data collection and analysis for key findings, such as the consistent loss of smaller farming operations and decrease of farmers by demographics. Nonetheless, it does provide some important information and given the critical nature of food and fiber production, it’s important to understand as much as possible about the agricultural landscape.

What the USDA 2022 Census of Agriculture Means for Arizona

Arizona is no exception to the accelerated rate of farm loss and consolidation. The past five years saw a steeper drop in the number of farms in Arizona as compared to the national average. Between 2017 and 2022, 2,376 Arizona farms went out of business – a 12% reduction. Small farms unable to make a living for their operators accounted for most of the losses. Nine out of ten of the farms that were shutdown prior to 2022 made less than $1,000 during the entire year. A large majority of farms included in the state’s census data, over 70%, recorded gross sales of less than $5,000, representing less than 0.2% of Arizona's total agricultural sales.

While some say a loss of nearly 500 farms a year may not produce any major effects in the state’s economy or significantly affect total state agricultural production, the loss of thousands of small-scale farms can impact the availability of food access points for isolated communities, prevent a culture of growing more hyperlocal, local, and regional crops to create resilience, and discourage the entry of new, diverse, and younger farmers. Small-scale farms can also provide benefits such as nutrition education, mental wellness and therapy, workforce training, and food sovereignty.

Just as national trends point to larger acreage farms and those same large farms benefiting the most from increased farm revenues, the census data for Arizona reveals the same pattern.

The value of production in Arizona farms and ranches increased from $3.85B in 2017 to $5.20B in 2022, but most of that increase was felt by larger farms growing specific crops – durum wheat, corn for silage, and several forage crops.

When it comes to one of the state's most productive agricultural areas – forage crops – the growth has not been even among farmers, census data indicates. Over the past twenty years, the amount of land dedicated to forage crops in Arizona grew from 289,334 acres to 423,246 acres. While the acreage doubled, the number of farms involved in the business only grew by about 10%.

Arizona farmers, like the national average, are older and aging faster than new ones entering the space. Less than 5% of the state’s producers are under 35. This could be in part due to the access barriers of getting into farming without a secondary income or infrastructure support of small-scale operations, or that the attrition rate of beginning and smaller farmers in Arizona is high.

More than 60% of producers in Arizona are Native American, and the state has the largest concentration of American Indian farms. Arizona also has some of the highest rates of Native communities participating in tribal supplemental nutrition assistance programs. Support for Indian Country agriculture is crucial for achieving food sovereignty and resilience within Tribal communities.

Most farmers in Arizona, like the majority in the country, rely on secondary or off-farm income to cover their household expenses. Census data shows that of the farms lost in Arizona, 90% were not economically viable, and farming was not a significant share of their income. As young and beginning farmers are being encouraged to enter Arizona’s farming space, faced with census statistics that show small farms are not economically viable, one can’t help but question if they are entering a place where the overall system is not supportive of their long-term health and success.

Behind the Census Numbers

The 2022 census data results begs the question: does the current agriculture system really support small, diverse, & beginning farmers? While some attrition is normal for anyone entering a new industry, the rate at which small farms are being consistently lost indicates that the system is not supportive of them.

Small-scale farmers in Arizona are working together to address critical issues that the census data shows – persistent land loss, consolidation, an aging farm population – and other issues specific to Arizona, such as extreme heat, drought, and water shortages.

The past several years has also seen historic federal funding for rebuilding and localizing food systems and infrastructure, as well as policy developments. If, however, the overall food system structure is still perpetuating “get big or get out,” these significant investments will only be short-lived.

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsak said the census results were a “wake-up call” for everyone interested in preserving a thriving rural America and wanting to create a more resilient, expansive food system with opportunities for more farmers.

Since taking office in 2021, Vilsack has supported policies designed to simultaneously support large-scale production, and the influential corporations that profit from the system, while also investing in new markets and processing infrastructure for small and mid-size farms. Without simultaneously taking aggressive action to rein in corporate monopoly power through fair competition rules, enforcing antitrust laws, the Packers and Stockyards Act, and the Robinson Patman Acts, these investments will eventually fail, like others have. Without disaggregating some of the largest food, meat, and beverage companies in the world, the largest companies will continue their wash-rinse-repeat model of buying out smaller competitors and putting more family farms out of business.

Having the smallest number of family farms since 1850 is, indeed, a wake-up call to prioritize local, regional, and diverse producers. If not, the ag census will just be 6 million data points of lost opportunity.

To Learn More & Get Involved:

2022 Census of Agriculture by State - Arizona

America’s Farms and Ranches at a Glance - 2023 Edition

Read the 2022 Census of Agriculture highlights and easy-to-read summaries of key findings

Register for the upcoming American Farmland Trust (AFT) “Highlights from the 2022 Census of Agriculture” webinar with presenters from USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service

Explore AFT’s Farmland Information Center Census of Agriculture Data Dashboard

Join the Indigenous Food & Agriculture Intiative’s online webinar series “2022 Census of Agriculture Indian Country Stats, Facts & More”

Download Indigenous Food & Agriculture Regional Data Infographics detailing statistics and facts on Indian Country farming, agriculture, and food security; Southwest region here